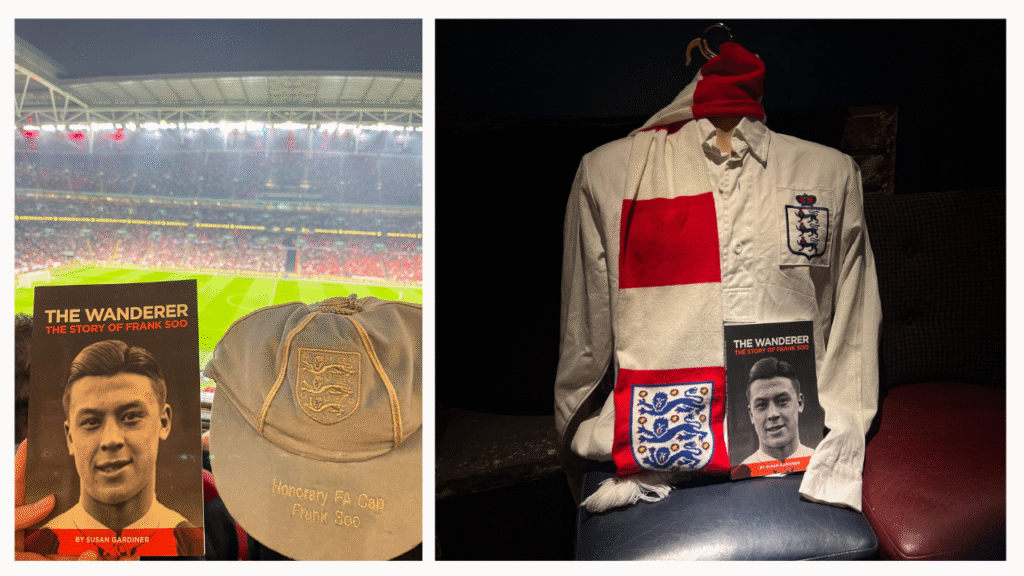

Wembley Stadium is usually a place for national excitement, but last night, during the England versus Wales fixture, it was the site of a profound, quiet reckoning. Before the whistle blew, a small, yet enormously significant piece of history was set right. Frank Soo’s family and the Frank Soo Foundation were finally presented with an honorary posthumous England cap, an official acknowledgment from the Football Association (FA) for the man who was, unequivocally, the first player of Asian descent to step onto the pitch for the Three Lions.

It took 83 years for the cap to find its way home.

Soo (1914–1991), born to a Chinese father and an English mother, was a star player in the 1930s. He made his professional debut for Stoke City in 1933, becoming the first player of Chinese origin in the English Football League (EFL). He went on to play 173 times for the Potters, even captaining the side alongside the great Stanley Matthews. The facts of his excellence were never in question.

Read More: Kick It Out and Frank Soo Foundation Unite to Confront Anti-ESEA Racism in British Football

His international breakthrough came on May 9, 1942, against Wales. He played nine total appearances for England during the war. That achievement established him as the first person of colour to represent the national side.

But institutional procedure effectively scrubbed his name from the record. The FA did not officially recognize any matches played during the Second World War. This decision, made on administrative grounds, denied him an official cap. It turned a national pioneer into a historical footnote.

The Price of Erasure

This historical silence did not happen in a vacuum. It was one mechanism of exclusion, a quiet counterpart to the overt racism that denied Black footballer Jack Leslie his chance to play for England 17 years earlier in 1925. Leslie was selected but barred solely due to the colour of his skin. Soo, conversely, was allowed to play, only to have the achievement procedurally stripped of its validation.

As Matt Tiller of The Jack Leslie Campaign put it, both stories share a striking manner: “Both were largely forgotten for decades”.

This institutional denial was reinforced by media prejudice. Soo faced a highly damaging, derogatory cartoon published during the war, which questioned his suitability for representing England based on his Chinese background. Frank Soo Foundation chair Alan Lau believes this public attack “had a detrimental effect on his football career”. The mixed heritage that made his accomplishment so unique also made him a target.

Read More: Frank Soo: England’s First Asian Footballer to be Inducted into Hall of Fame

After the war, the bias seemed to follow him off the pitch. He went on to become an internationally successful manager, coaching the Norway national team for the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki and guiding Sweden’s Djurgardens IF to the Allsvenskan league title in 1954–55. Yet, after a short stint managing Scunthorpe United in 1959–60, he “struggled to find work” in Britain. The fact that a league-title-winning international coach had to seek opportunities predominantly abroad speaks volumes about the limitations placed on non-white talent in the UK system at the time.

History as a Policy Tool

The official recognition at Wembley last night, fittingly during East and South-East Asian (ESEA) Heritage Month, is less about nostalgia and more about systemic action. It is a hard-won victory for the Frank Soo Foundation, a grassroots organization that works to share Soo’s life, promote football participation within ESEA communities, and foster a positive view of Chinese individuals in Britain.

The Foundation’s efforts are essential because the institutional indifference Soo faced has an urgent modern parallel. Racism directed at ESEA communities in football is a demonstrable crisis. Over a recent six-season period, Kick It Out reported a total of 377 instances of player abuse targeting only nine different ESEA footballers. A staggering 94% of that abuse was aimed at one high-profile individual, former Tottenham forward Son Heung-Min.

The bias is also expanding into the stands. Reports of abuse targeting ESEA fans rose sharply, increasing from 13 reports in one season to 48 reports in the subsequent season.

The Foundation is directly combating this by leveraging history to drive policy. They have established a new reporting relationship with Kick It Out. This partnership focuses on coordinating support for victims and ensuring these incidents are taken seriously. Kick It Out COO Hollie Varney noted that reports of racism toward ESEA communities often “seem to be taken less seriously, and this relationship seeks to address that by raising awareness”.

Read More: INTERVIEW: Author Susan Gardiner discusses her book on British Chinese footballer Frank Soo

By forcing the FA to formally acknowledge Soo, the Foundation ensures that the ESEA community is no longer perceived as perpetually new to the English game. His legacy provides a visible, historical reference point against which modern marginalization can be measured.

Dal Darroch, the FA’s head of diversity and inclusion strategic programmes, emphasized this point regarding the cap presentation. He said: “Frank Soo’s immense contribution to English football deserves lasting recognition. A player of great skill on the pitch, and of determination and resilience off it, his story lives on today. His pioneering legacy continues to inspire young players now, and will continue to do so for generations to come”.

Alan Lau added that he and the Soo family “cannot wait to see the impact this recognition will have on East and South East Asian communities and for English football”.

The scene at Wembley, though small in scope, was powerful. It confirms that the FA can, and must, reckon with its history of exclusion. The cap is a marker, an important symbolic closure to a wrong. But the real work is just beginning. It requires consistent action to ensure that the systemic biases that erased the first ESEA pioneer are not allowed to silence the generations of talent who follow him.