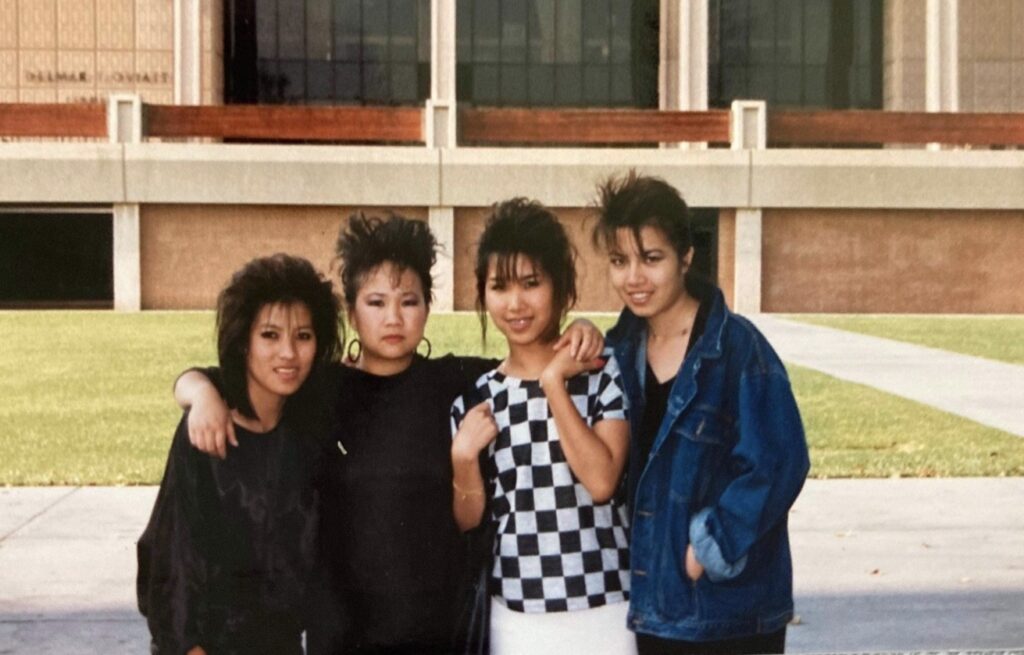

For many in the West, the narrative of Vietnam and its diaspora remains stubbornly fixed: either the brutal imagery of war or the glittering excess of recent cinematic portrayals. But filmmaker Elizabeth Ai’s debut feature documentary, “New Wave,” offers a vital and alternative perspective. Instead of focusing on familiar tropes, Ai plunges into the electric energy of the 1980s Vietnamese New Wave music scene in Southern California, a subculture born from the experiences of young refugees finding their feet – and a beat – in a new land.

The late 1970s and 1980s saw a significant influx of Vietnamese refugees to the United States following the end of the Vietnam War. These individuals and families, often carrying the weight of immense loss and displacement, sought to rebuild their lives in a new and unfamiliar country. For the younger generation, straddling two worlds – the memories and traditions of their homeland and the burgeoning culture of their new environment – presented unique challenges. It was within this context that the Vietnamese New Wave scene emerged, a vibrant expression of youthful rebellion and a search for identity.

The film itself weaves together archival footage of the era’s distinctive fashion and performances with intimate interviews. Figures like DJ Ian Nguyen and Lynda Trang Đài, the so-called “Vietnamese Madonna,” vividly recall the energy of the underground clubs and the liberating power of the music. This wasn’t simply imitation of Western new wave; it was a unique fusion, often incorporating Vietnamese lyrics and sensibilities, providing a soundtrack for a community forging its own identity.

Speaking about the initial concept, Ai explains, “Initially, I thought of the project as preserving a slice of history in the Vietnamese diaspora. I imagined it as something like VH1 Behind the Music—not that I aspired to that format, but it was a straightforward idea.” However, as she began to engage with the community, interviewing “fans, pop stars, producers,” the project took on a far deeper significance. “It became clear that this was more than nostalgia; it was about survival and identity.”

The film, which has garnered awards and recognition at festivals like Tribeca, initially set out to document the mile-high hair and synthesised sounds that defined this unique musical moment. Yet, as Ai continued her work, a more personal undercurrent began to surface, prompted by probing questions from her editors and advisors. “They began asking: Why are you avoid

Ai’s initial resistance to revisiting painful histories gradually gave way, a shift catalysed by a simple yet profound question from her young daughter: “‘Where is your mama? Where’s your papa?’ I had never explained that to anyone,” Ai recounts. “I’d always just said, Oh, I’m not close with my parents, and moved on. But when she asked, it stopped me in my tracks. I realised I couldn’t just dismiss her. I had to be honest with her.”

This pivotal moment led Ai to re-examine material she had previously cut, details concerning “trauma, fleeing, being separated from family.” The result was a fundamental restructuring of the film. “It starts as a music documentary—introducing the world, the people, the sound. But I was quietly contemplating: Why does this matter to me? At first, I tried to stay objective. Eventually, my personal story was woven into the fabric.”

While acknowledging the underlying trauma of displacement, “New Wave” also shines a light on the celebratory aspect of the Vietnamese American experience. The music, the fashion, the very act of creating a vibrant subculture in a new land, becomes an act of defiance and a source of joy. Ai initially questioned if a film about the Vietnamese experience could be “joyful and celebratory? One where we can laugh, dance, and celebrate without rehashing painful memories?” Ultimately, she finds a way to hold both the pain and the exuberance within the same frame.

Navigating the sensitivities of sharing family history proved to be a significant hurdle. Ai describes a cultural reluctance to dwell on the past, a survival mechanism ingrained in those who have experienced displacement. “When I asked my relatives questions, the response was often, Why are you asking? You were there. I grew up in a household where love was shown through action—food on the table, clean clothes—not through deep conversations.” Despite this ingrained reticence, Ai’s persistent questioning eventually yielded glimpses into the past, though often in brief and carefully guarded moments.

The journey of bringing “New Wave” to the screen was also a lesson in the often-precarious world of independent filmmaking finance. “It was like flying a plane while building it,” Ai explains. “I was applying for grants whilst also making the film, right up through the final stages. We had support from about 20 funders, plus a Kickstarter campaign where hundreds of people contributed—sometimes just £5 or £10. Without them, this film wouldn’t exist.” This patchwork of funding, from philanthropic organisations to individual contributions, highlights the dedication required to tell stories outside of mainstream commercial interests. “No one on the team worked for free, and I’m proud of that,” Ai states, emphasising the ethical considerations that guided the production.

As “New Wave” has begun to reach audiences, the impact has been deeply personal for Ai. Reflecting on the audience response, she shares a particularly moving moment. “One of my favourite moments was getting a note from someone who said the film helped them heal their relationship with their mother. That’s everything. People say, ‘If you can touch just one person…’—and I think we’ve done that, many times over.” This connection with viewers, the ability of the film to resonate on an emotional level and even facilitate healing, underscores the profound power of storytelling that Ai sought to unlock.

Read More: 50 Years On: Vietnamese Boat People Remembered in New Rich Mix Exhibition

Ultimately, Ai hopes “New Wave” will reach a wide audience and spark meaningful dialogue. “I want as many people as possible who need this film to see it. Honestly, I’d love to give it away for free. But we also need to support the team.” She envisions the film as a catalyst for “intergenerational dialogue,” encouraging families to “talk about their feelings more openly.” For aspiring documentary filmmakers, particularly those tackling personal or culturally specific stories, Ai offers simple yet crucial advice: “There’s no magic formula. I wish there were. But my advice is simple: don’t give up. Keep applying for grants. Keep going, even after rejection. That persistence—that ability to keep showing up—is the most important thing. And beyond funding, find your people. Find those who truly believe in you and won’t let you quit.”

“New Wave” is a vital contribution to understanding the multifaceted experiences of the Vietnamese diaspora, using the infectious energy of a musical subculture as a vehicle for exploring deeper truths about identity, memory, and the enduring impact of displacement.

UK audiences still have a chance to experience this compelling film. Tickets are available for screenings presented by MilkTea Films in:

Manchester | Treehouse Hotel | 16 May

Birmingham | Mockingbird Cinema | 20 May

For audiences in the US and beyond, head to New Wave more screening dates and information on how to watch New Wave.