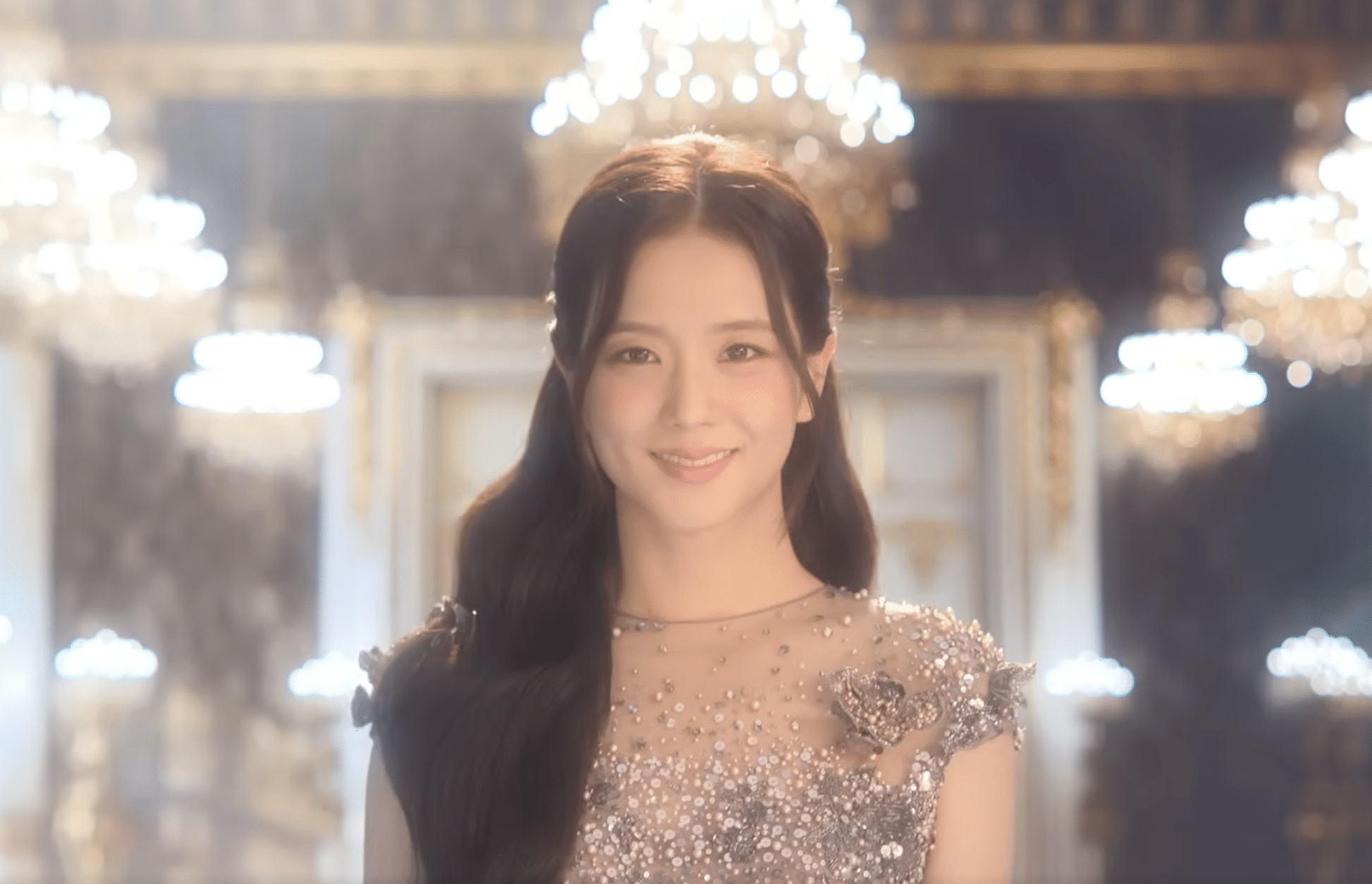

Mari Yamamoto has always understood that a great story leaves you with a feeling that’s hard to explain. “It leaves you feeling like somebody is both holding and squishing your heart at the same time,” she says, referencing the sensation a truly moving script gives you. But for her latest film, director Hikari’s gentle and beautiful Rental Family, that feeling became something deeply personal.

The film, which has earned praise for its honest look at modern loneliness in Tokyo, centers on a unique service that hires actors to pose as family members or companions for those who need them. Yamamoto plays Aiko Nakajima, a seasoned member of the rental company whose roles often expose the challenging, darker side of transactional emotion. For Yamamoto, reading the script came during a “catastrophically sad time in my life” following the loss of her father.

“Reading the script gave me a sense of hope,” she explains. “Because of all the fatherhood themes in the script, it felt like almost a sign from my own father saying, ‘Go out there, and you’re going to find people who care about you. You will find connection. You can’t replace a parent, but you will find those things.’ I found that to be extremely comforting and hopeful.”

The movie’s premise might raise eyebrows in the West, but Yamamoto, who grew up in Tokyo and London, approached it with a natural understanding. “As a Japanese person reading the script, the idea of a rental family is not too far-fetched,” she says. She explains that the flourishing of this model stems from a specific cultural dynamic.

Loneliness is everywhere, but Japan found a peculiar solution because of its particular “love language,” which values subtlety and not burdening family. This way of communicating— “making sure they’re okay, but not bothering them, not burdening them” — creates a delicate “balancing act of wanting to be intimate, but sort of keeping it at a distance.”

Yamamoto sees the services as a symptom of a culture of conformity, where people are raised to be so considerate of others that they often cannot “directly ask for something you want.” This makes turning to a paid service easier, since you can simply “state what you want and then you will get it without feeling guilt or shame about it.” She ultimately defends the practice, saying that having “somewhere you can turn to instead of falling through the cracks of loneliness” is a “positive alternative.”

To prepare for Aiko, Yamamoto spent time building a rich backstory with Hikari. She says Aiko needed that deep foundation to fully realize her motivation on screen. In a fascinating detail, she mentions she visited a real service with the director, one that calls itself the “all-women handyman company.”

This initial framing lowers the barrier for entry, she notes, because “It might start with something like, ‘Can you go grocery shopping for me because I have COVID and I don’t have anyone to ask?’ or ‘Can you change the AC filter for me?’ But what essentially starts as a tiny errand leads to a deeper need for companionship, for connection.” This research helped her grasp “the necessity of this business,” realizing people who rely on it often have nowhere else to go.

She also pointed to the very real suffering that informs some of the movie’s high-stakes emotional scenarios. While shooting the film, news broke that a lesbian couple in Japan had been granted refugee status in Canada because of discrimination by family and employers. That devastating reality “made the stakes for the wedding scene, for instance, so high,” she says. “I knew that there were real people who were suffering these consequences.”

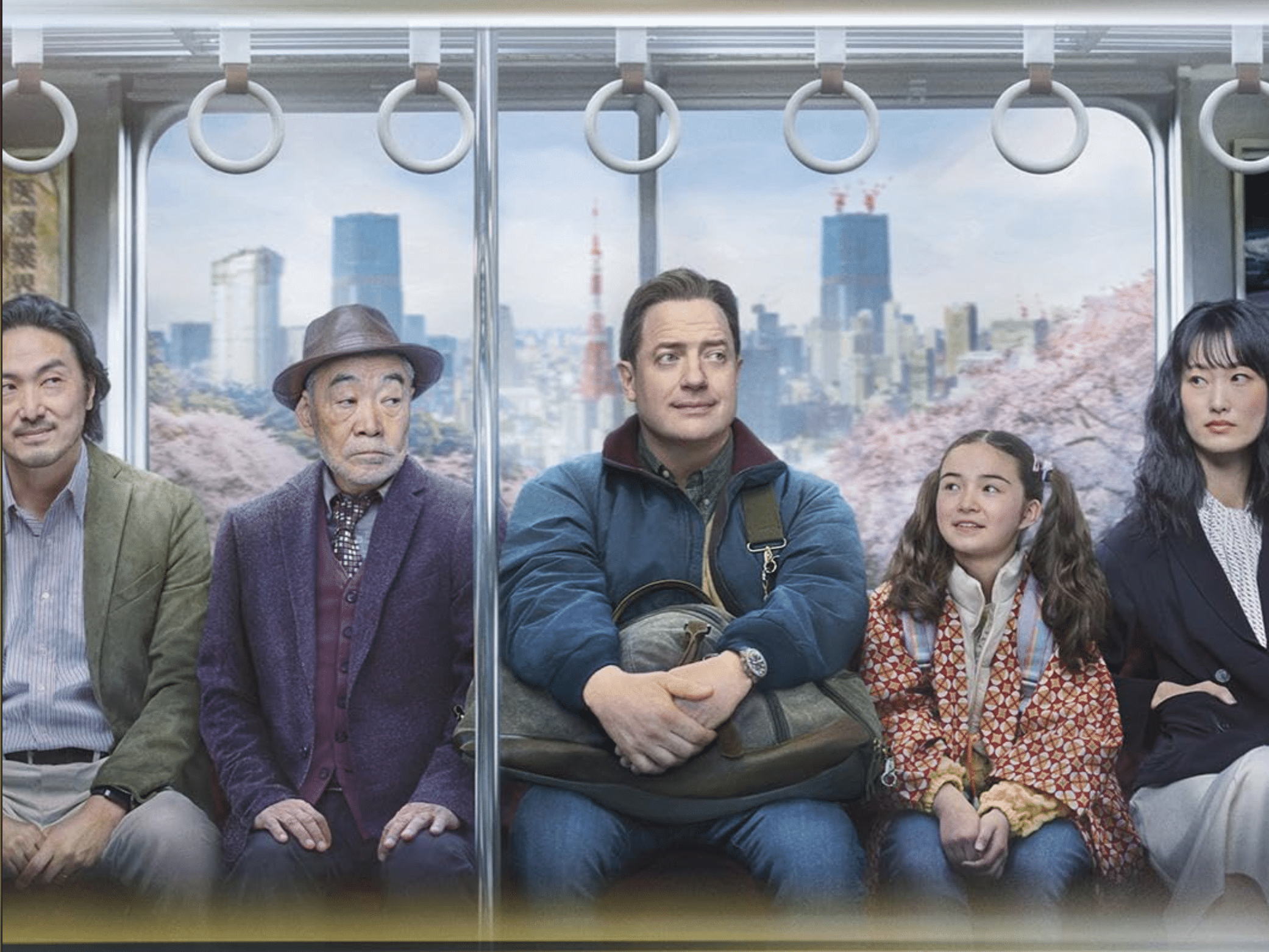

Of course, a film this heartfelt and moving needs a gentle center, and that’s Brendan Fraser. Fraser, fresh off his Oscar win, leads the film as the American outsider, Phillip Vandarpleog. Yamamoto confirms everything you hope about the veteran star. “Working with Brendan Fraser—everybody has an idea of who he is, that he’s this incredibly wonderful, joyful, sweet, soft teddy bear person. And he’s everything you think he is, and so much more,” she states. She was struck by the unexpected level of consideration and “generosity that he extended to all of us on set—not just the cast, but also the crew.”

The star power didn’t stop there. Akira Emoto, a true legend of Japanese cinema, plays a key role opposite Fraser. Yamamoto remembers being in awe, having grown up watching his films. She recalls watching him work on her days off, particularly the scene where he talks about the 8 million gods in Japan. “I was just crying behind the monitor because I got to be in a film with Brendan Fraser and this legend I’ve always looked up to,” she says. “That’s something that’ll always stay with me.”

Ultimately, the film asks what makes a relationship real. For Yamamoto, the line she delivers in the film, “Sometimes the story we tell ourselves becomes the truth,” holds the key. She defines the term as chosen family. “It’s what you choose, right? Chosen family is a story we tell ourselves,” she explains.

“We weren’t born into the same family, but you and I choose to be like a chosen family. And that’s our story, and that’s what we create. So that’s an example of a story we tell ourselves that becomes true, I think.” And her final word on the matter is simple and freeing: “If you’re not hurting anybody, and if you’re creating your own reality and happiness, I think who’s to judge and who’s to say you can’t do that.”