The 30th Busan International Film Festival (BIFF) recently provided a stark look at the financial crisis hitting South Korea’s film sector. The global success of K-content is unmistakable—the Korean Wave is one of the world’s most powerful cultural exports. But look closer, and you see a troubling economic paradox: the nation’s local film industry is in its biggest downturn in almost two decades, excluding the pandemic years.

Revenue fell by 33% to $293 million (KRW407.9bn) in the first half of 2025. Admissions dropped by 32.5% to just 42.5 million over the same period. Meanwhile, global streaming giants are celebrating record-breaking Korean-inspired content. This gap reveals a broken economic feedback loop where global demand for Korean IP is not translating into local profitability.

Read More: South Korea Selects Park Chan-wook’s ‘No Other Choice’ for Oscar Consideration

The crisis is deep enough that the very future of local filmmaking is in doubt. The five major Korean production-distribution groups—including powerhouses like CJ ENM and Lotte Entertainment—are planning to release only 10 to 14 Korean commercial films in 2025, a brutal cutback from the 35 films released in both 2023 and 2024. As one academic observed, “It’s perhaps better to think of Korea’s film industry as a canary in the coal mine that foreshadows what will happen, indeed is happening, in other markets when those audiences also opt for online over in-person cinema.”

View this post on Instagram

The ‘KPop Demon Hunters’ Test Case

The animated feature KPop Demon Hunters is a perfect example of this dilemma. The film became an all-time global hit for Netflix, celebrating and showcasing Korean culture, but its success offers local Korean studios zero financial benefit.

The film’s Canadian-Korean creator, Maggie Kang, was celebrated at BIFF’s Creative Asia event for her meticulous work ensuring the film’s cultural authenticity. Yet, the financing model reveals the problem: there was not a drop of Korean investment in the Sony Animation and Netflix production.

Read More: Zhang Lu and Shu Qi Win Top Honors at the Busan International Film Festival

This means that while the film boosts Korea’s soft power, technically not a penny of revenue will flow back to Korea’s struggling local studios. The creator, Maggie Kang, emphasized the need for authenticity, but the financial structure makes the local industry entirely reliant on foreign money to tell its own cultural stories. “I think that’s really the only way that K-content can reach an even broader audience and become even more global than it is right now,” Kang said, perhaps unintentionally highlighting the necessity of foreign distribution for global reach.

The question becomes: is this a modern form of cultural extraction, where foreign streamers harvest IP, talent, and cultural flavor without funding the national infrastructure that created them?

Talent Drain and the Search for a Lifeline

The struggles of the local film sector are forcing a talent shift that further benefits the streamers. As financing for independent cinema shrinks, new directors and established actors alike are migrating toward television and high-budget streaming series. The fear of financial ruin is real.

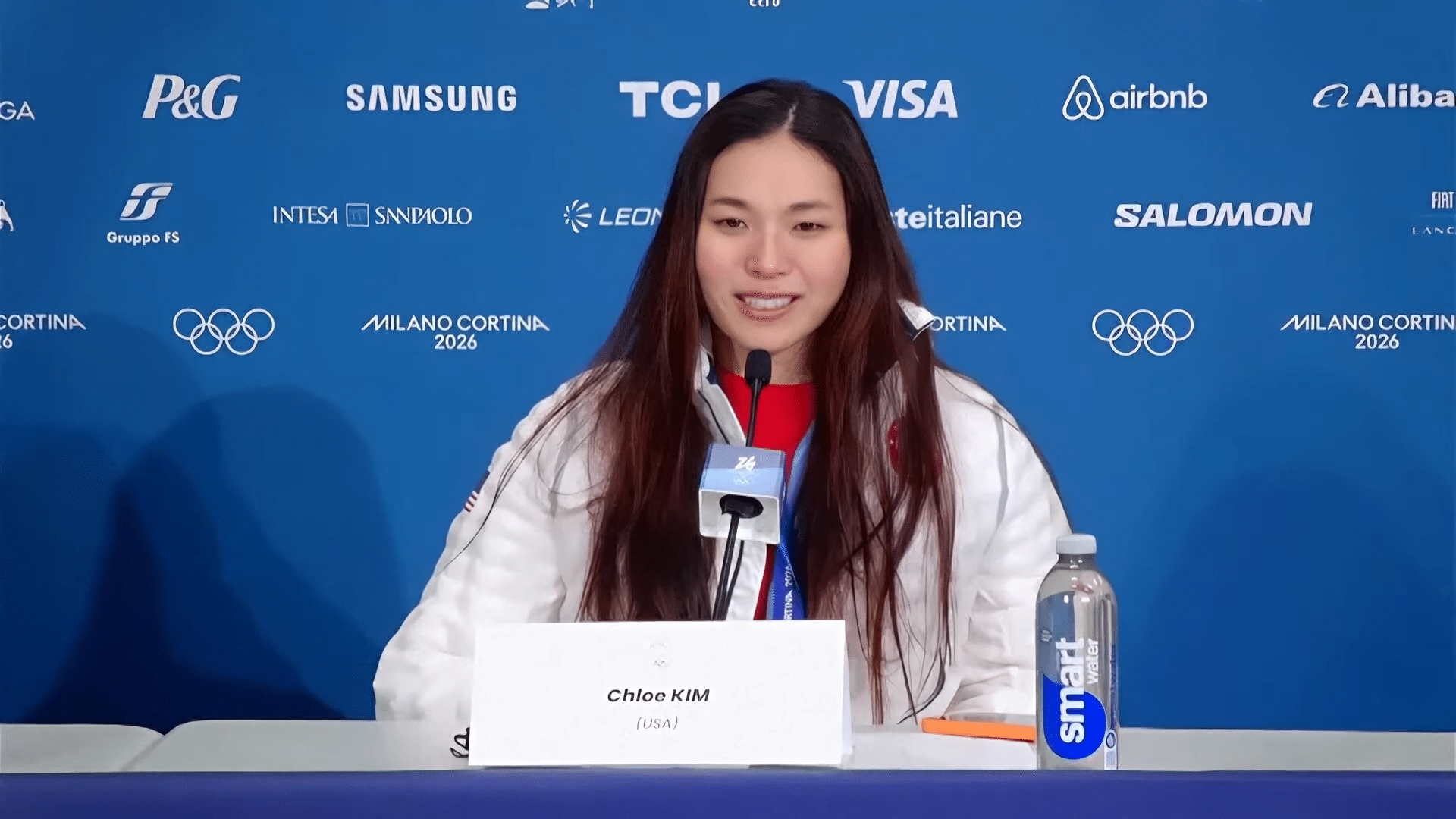

During the press conference for the festival’s opening film, No Other Choice, the crisis became personal. Directed by Park Chan-wook and starring global names like Lee Byung-hun (Squid Game) and Son Ye-jin, the film is being used as a symbolic push to save the theater business. Even this elite group of artists expressed genuine anxiety.

Actor Park Hee-soon summed up the fear candidly: “I’ve made a living through films, but now it feels like relying solely on films could lead to starvation.”

Read More: ‘Bon Appétit, Your Majesty,’ a New K-Drama, Is Netflix’s Most Watched Show Globally

Lee Byung-hun echoed that concern, making a direct link between the film’s theme of unemployment and the film world itself. “During our visits to Venice and Toronto film festivals, we were often asked if the film industry feels a sense of crisis, much like the paper industry in the film,” he said. “While the decline of paper usage affects the paper industry, I believe theaters face even greater challenges.”

To counteract this, the market is urgently turning to co-production and co-operation. Traditionally self-sufficient film industries like Korea and Japan are now forced to look outside their borders to pool resources and expand distribution networks. The Asian Contents & Film Market (ACFM) was noticeably busier this year, focusing on new partners from Canada, Latin America, and the Middle East, a clear signal that the financial survival of the Korean film business requires it to become less “Korean” and more international in its structure.

If the industry can’t find a way to make local cinema financially viable, the paradox of K-Culture will only widen: more global fame, less local funding.