A Personal Journey Illuminates a Nation’s Story

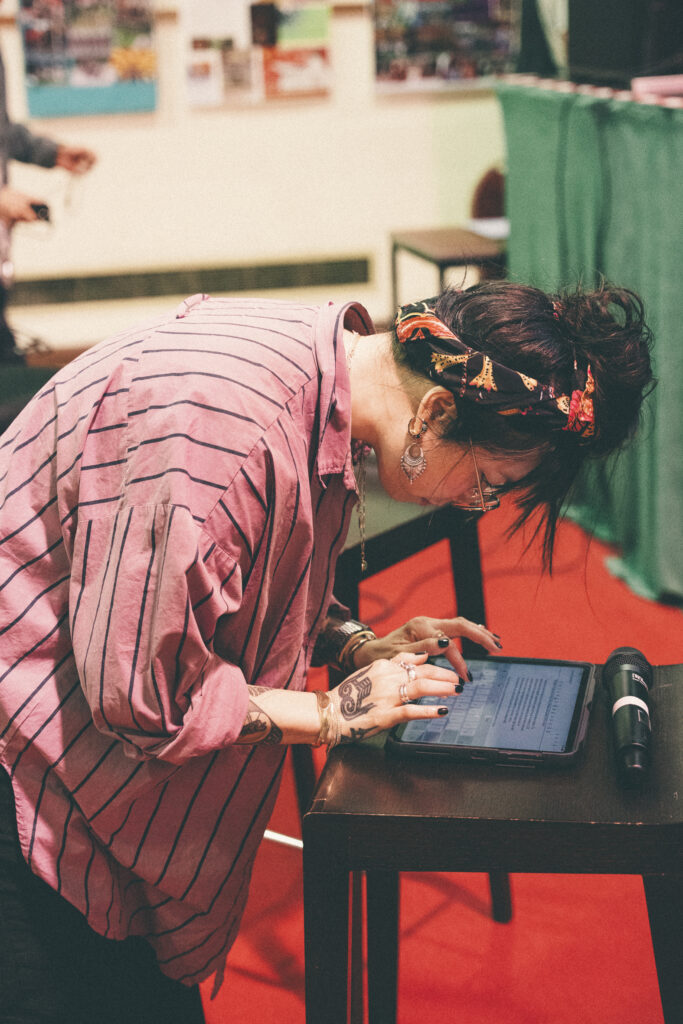

For Tuyết Vân Huỳnh, the idea for a film festival began in 2019, sparked by a simple, yet profound, question: “Why isn’t Vietnamese cinema visible in British cinemas?” This inquiry, rooted in her Master’s studies in film programming and curating, set her on a path of discovery that would not only reshape her understanding of her own mixed Vietnamese and Chinese heritage but also bring unseen cinematic treasures to UK audiences.

Her initial exploration led her to Hanoi, Tuyết, a student working on her thesis, proposed the idea of curating the first Vietnamese film festival in the UK. The Institute, surprisingly, was “receptive and allowed me to access their archives”. That week was transformative. She met filmmakers, producers, and queer creatives, watching over 50 films. “I realised there was a real, tangible programme waiting to be shaped,” she explains.

This drive to connect with her identity through film was a long time coming. Growing up in the 1990s, Tuyết notes, her Vietnamese side “felt somewhat hidden”. While her Chinese heritage was known, Vietnam “not so much”. She consumed Hong Kong, Chinese, English, and American cinema, but it wasn’t until 2013, when she started working in the arts, that she truly began exploring her Vietnamese identity. “I was 30 and realised I had never seen a Vietnamese film. That shocked me. It was a core part of who I am, and yet I hadn’t seen it reflected on screen,” she shares. This realisation “opened the floodgates” for a curiosity that has only grown.

More Than Just Films: Star, Nhà, Ease

The festival’s name, Star Nhà Ease, carries deep meaning. Developed with British Vietnamese graphic designer Lợi Xuân Ly and Vietnamese archivist Cường Minh Bá Phạm, the name emerged from brainstorming ideas where the herb Star Anise emerged and “we all light up at the sound of it.”

Tuyết explains the symbolism: “Star: a guiding light, symbolising the journey out of Vietnam. Nhà: means ‘home’ in Vietnamese, representing the search for belonging. Ease: the emotional state of finally finding a place where you feel safe and accepted.” For Tuyết, the name “encapsulates the migration journey—leaving, arriving, and healing”.

This personal lens heavily influences her curatorial choices. “This is our second year, and I really see the festival as a personal journey of discovering what being Vietnamese means to me,” she states. While the first season focused on positioning Vietnamese cinema within its own context, “not through the Western or Hollywood lens,” Season 2 marks a shift.

Tuyết was “done with war narratives”. Her conversations with Vietnamese curators led her to the Đổi Mới era, a period when Vietnam began opening up to international collaboration, marked by “reimagining, experimentation, and a move away from state-owned narratives”. This focus felt like “a mirror to my own journey—acknowledging the trauma but also embracing the joy of being Vietnamese in Britain,” a joy that “runs through this season’s programming”.

The Unseen Challenges of Unearthing Cinema

Bringing a festival like Star Nhà Ease to life was not without its hurdles. “Money—always money! But also access and belief,” Tuyết candidly admits. A significant challenge involved “convincing a state-run Vietnamese archive to support a UK-based festival” and then “getting British public arts funders to understand why Vietnamese cinema matters here”.

It was a “two-fold” battle of navigating institutions in both countries, securing rights, and, ultimately, encouraging people to attend. “Marketing was hard with limited funds,” she recalls. “Vietnamese communities hadn’t seen themselves on screen before and hadn’t been invited into cinema spaces like these. So asking them to trust us and come was a huge challenge.”

The unearthing of “lost gems” is central to the festival’s mission. Take Hát Giữa Chiều Mưa (Singing in the Rainy Afternoon), a highlight from the Đổi Mới era. This period, from 1990 to 1994, is known in Vietnam for “instant noodle films”—”fast-paced, low-budget productions” that were the first to feature real film stars. Tuyết’s funding allowed her to spend two months in Vietnam, collaborating with local film clubs and organisations.

Read more: Star Nhà Ease Returns: Vietnamese Cinema Season 2 Explores Đổi Mới Era

It was during this time that a curator spotted Singing in the Rainy Afternoon in the Vietnamese Film Institute’s directory. “It turned out no one had actually seen it—people just knew it existed,” Tuyết explains. It had never been screened in a cinema or subtitled, remaining “buried in the archive”. The team watched it in a makeshift cinema room, with Tuyết’s translator providing a live interpretation. “We were all just stunned. We knew instantly: we have to bring this film to the public,” she recounts.

A Gateway to Connection and Understanding

The impact of Star Nhà Ease extends far beyond the screen, particularly for the Vietnamese diaspora. Tuyết observes that watching films together creates a “gateway” for conversations about complex histories that can be difficult for second-generation children to discuss with their parents. “The film does the speaking for us,” she suggests.

Emotional audience feedback from the first season underscored this. In Birmingham, a “mixed Vietnamese-English family and two elderly Southern Vietnamese individuals who had never been to a cinema before” stayed for the Q&As, leading to conversations so moving they brought tears to Tuyết’s eyes. A screening of Little Girl of Hanoi, a 1974 film about the American bombing of Hanoi seen through a child’s eyes, particularly resonated. “People cried,” Tuyết notes. One young woman said, “Watching that with my mum was incredible”.

Tuyết’s own experience with Little Girl of Hanoi mirrored this. After watching it for her Master’s, she asked her mother about it. Her mother had seen it when it first came out, during the unfolding events it depicted. “She said the whole cinema cried back then because it felt like a documentary,” Tuyết shares. When they watched it again together, her mother commented, “I don’t remember it being that traumatic,” a moment that “opened up a conversation between us that we had never had before”.

This ability to foster intergenerational dialogue is a core motivation for Tuyết. She wants audiences to feel “joy” and understand that “Vietnam is a vibrant, evolving place with diverse stories”. The goal is to move “beyond war narratives and show something new, especially to elders and second- and third-generation Vietnamese folks”. For many dealing with “inherited trauma from our parents,” these films offer a way to “reconnect, to renew how we think about Vietnam and see ourselves in its stories”.

Reframing Narratives and Building for the Future

Tuyết stresses the importance of reframing narratives, telling Vietnamese stories through their own eyes rather than through a Western lens, which often focuses solely on war. “It’s essential,” she states. While early Vietnamese films were “grounded in reality” and “shaped by political narratives,” Tuyết believes “the next generation has more to offer”. For her, reframing “is not about discarding the past; it’s about moving forward with it. It’s saying: Yes, that history exists. But so does joy. So does complexity. So does love. Let’s make space for all of that too.”

The festival’s multidisciplinary approach, incorporating music, poetry, and visual arts, reflects this expansive vision. “This isn’t just a film season. It’s a cultural experience,” Tuyết asserts. This layering of elements aims to show that “Vietnamese artists, whether emerging or established, are multifaceted”. It’s about proclaiming: “Boom! This is Vietnam—dynamic, diverse, and alive.”

A significant future undertaking is the creation of the first bilingual digital archive of Vietnamese cinema, a “massive undertaking” motivated by Tuyết’s own struggles in finding information about Vietnamese cinema for her research. This archive will be “free, bilingual, and evolving,” serving as a lasting resource. “I want others to be able to discover what I’ve found—because it’s beautiful, and it’s helped me grow,” she says.

Read more: ‘TAPE’ (2024) Remake: Why Hong Kong’s New Film Challenges How We See Accountability

Star Nhà Ease is presented by Tuyết Vân Huỳnh. It receives support from Arts Council England, the British Council Connections Through Culture programme, and the BFI Audience Projects Fund, which awards funds from the National Lottery. The season works in collaboration with The Centre for Assistance and Development of Movie Talents (TPD) and the Vietnam Film Institute. Its shorts programme receives additional support from Varan Hanoi.

For more information about the festival click here